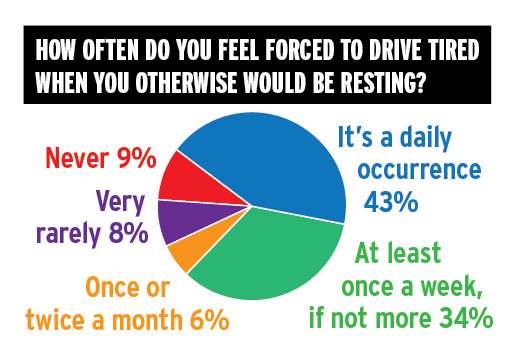

Nearly eight in 10 truck operators say they feel pressured by either their company or the hours of service rule to drive tired on at least a weekly basis, according to recent Overdrive polling. Almost half reported driving fatigued on a daily basis.

Those numbers highlight a deficiency in the federal government’s primary tool – HOS limits – for dealing with potential driver fatigue. While requiring drivers to take at least 10 off-duty hours out of every 24, the regulations can’t control the off-duty period.

They don’t account for a restless night’s sleep, undetected sleep apnea or foolish time management. In the fatal Walmart truck crash involving comedian Tracy Morgan, the truck driver was legal on hours even though he hadn’t slept for more than 24 hours prior to the wreck.

Fatigue-monitoring technology promises to drastically narrow the often vast gap between the government’s formula for alertness and the reality of frequent fatigue. Such systems applied to individual drivers could theoretically replace the clock-based system that attempts to cover all drivers.

The systems could help usher in a regulatory protocol where “drivers with good habits go further, longer,” says Richard Kaplan, chief executive officer of Curaegis, which makes a wearable device that yields predictive and real-time fatigue assessments.

“Drivers who aren’t as healthy or who stay out all night or whatever are not able to stay out so long.”

While the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration is studying some of these technologies, it’s years away from possible consideration of an HOS revision that would even begin to incorporate them.

Things are happening much faster in the private sector. Dashcam systems with fatigue-monitoring potential are coming to market rapidly, and a variety of systems that don’t use cameras are starting to make headway in trucking. Fleet customers are getting an increasingly accurate picture of drivers’ fatigue levels, which never has been available. Countering that, though, is potential driver resistance over privacy issues, especially with driver-facing dashcams.

Don Osterberg, formerly safety head with Schneider National, well knows the challenges fleets face, as well as the huge effect fatigue has on safety. He’s an adviser today for SmartDrive, one of the leading road-facing and multi-camera systems.

“There are technologies and programs that we could operationalize today if we were serious about getting after this problem of fatigued driving,” Osterberg says.

Such systems could measure driver fatigue levels during a duty shift or just before it and do much better than the “outdated” hours rule, says John Elliott, president of Michigan-based expediting fleet Load One. Cameras, performance monitors “and biometrics will better determine a driver’s available hours,” he says.

How much drowsy driving contributes to the annual toll of highway fatalities – 37,461 in 2016 – is a matter of speculation due to the difficulty of identifying fatigue as a factor.

No one doubts that it’s a significant factor, and most observers believe fatigued driving is strongly underreported in crash analyses.

“Unless a driver admits to law enforcement they fell asleep, it won’t be recorded as a fatigue–related crash,” says Don Osterberg. Available data “dramatically underrepresents the issue of fatigue” in severe truck crashes.

Fatigue plays a part in 30 to 40 percent of high–severity truck–involved accidents, Osterberg estimates. If he’s correct, nearly 1,500 of the annual truck–involved fatalities (4,317 in 2016) can be blamed at least in part on fatigued driving.

In March, former National Highway Traffic Safety Administrator Mark Rosekind said fatigue is a factor in 20 percent of crashes. This was based in part on a series of transportation disasters, only some involving trucks, investigated by the National Transportation Safety Board.

Elliott envisions a system where a driver approaching a maximum limit under current hours regs “might be good to drive for six more hours” based on current data. Another driver in the same situation, however, “might only be good for 30 minutes. It comes down to the ability to measure the human body to better understand and determine what is safe.”

He believes such a system will “allow these guys to have much better” health outcomes and quality of life than exists today, given the close relationships between fatigue, stress and health.

What might work best, Osterberg says, is using combined technologies. One layer, he says, could be psychomotor vigilance task tests developed by NASA, where answering test questions determines an individual’s performance level. PVTs also have been used in driver fatigue research.

In Osterberg’s example, a PVT test could be combined with use of a wristwatch-like actigraph that, by measuring body movement, assesses sleep volume and quality.

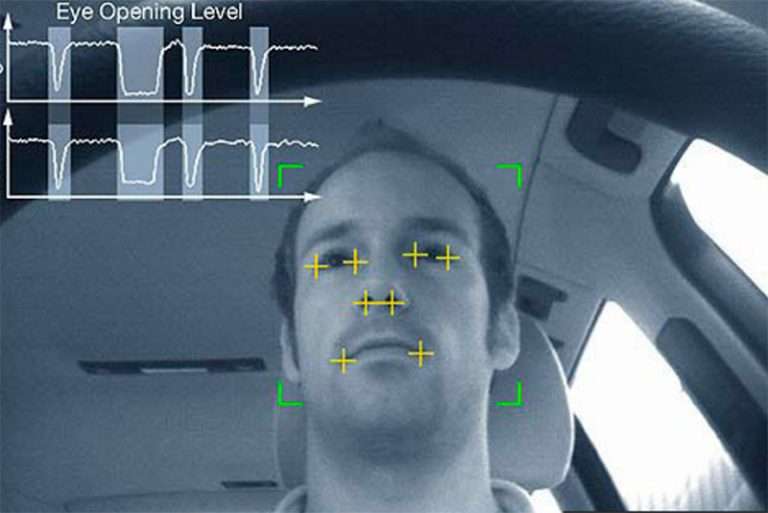

“We could get a pretty refined sense of what the driver’s capable of doing in a given day,” he says, adding that video monitoring and facial mapping also could be used.

There are other fatigue monitoring technologies, too. One wearable device measures brain waves, and another measures head movements as indicators of mirror checks, micro-sleeps and distraction. Some wearables capture heart and respiration rates, which can be fatigue indicators.

Another system is baked into Blue Tree Systems’ electronic logging device/telematics platform. It can measure the time between lifting off the accelerator and using the brake. Fatigued drivers tend to lag in anticipating road or traffic changes, so they log shorter times between the two pedals.

Fleets’ concern for safety isn’t the only thing advancing fatigue monitoring technology within trucking. Elements of the systems that are driving autonomous trucking also contribute. For example, the same tech that tracks lane departure and following distance for autopilot-type systems also can be programmed to detect on-highway behavioral patterns indicating a driver could be fatigued or distracted.

Whatever monitoring system is used, what happens after detection is an open question. The basic approach is for a dispatcher to talk with an apparently fatigued driver, trying to assess if the driver can safely reach his destination, or if some mitigation is needed, such as briefly getting out of the truck or taking a nap.

Or a fleet could take a more aggressive approach, giving primary weight to the data and ensuring that fatigued drivers come off the road as soon as possible or never start driving to begin with.

“It will bring more challenges to the industry,” Elliott says. “A driver may leave out, and in two hours the system determines he’s in need of rest. Say the driver just had a 10-hour break period, but for nine of those hours, he was unable to sleep for whatever reason. Say he didn’t feel well. If the ultimate goal is to continue to improve safety, I think we’ll have to address those hurdles as we go. A driver may not like the fact that we’re going to recognize his problems. Say he’s got a sleep issue or another medical issue. But we’d rather have that addressed for him and the motoring public” than not.

Driver-facing dashcams, paired with the right equipment, can measure length and frequency of eyelid blinks and head nods. The technology has generated the strongest driver opposition among all fatigue monitoring systems.

Other hurdles could be legal, given medical privacy laws and the like. “I think you might see some of those legal battles fought outside of trucking,” Elliott says, citing airline pilots and bus drivers, since they are responsible for passengers, not freight. Then trucking would reckon with whatever gets codified in those industries.

“In an industry where 4,000 truck-involved fatalities occur every year,” asks Osterberg, “do we have a moral obligation as transportation professionals … to leverage indicators of fatigue as a way of mitigating future crash risk? I don’t believe for a second that regulators are going to go there anytime soon. But carriers sequentially will have to demonstrate the efficacy of interventions” to the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Potential intervention goes beyond simply detecting fatigue and warning the driver. Many of the fatigue-monitoring systems offer remedial material for fleets to use in helping drivers learn about sleep patterns, naps and related fatigue mitigations.

Longtime owner-operator and small-fleet owner Harold Hoffman of Springfield, Missouri, believes there’s more fruit to be borne in teaching fatigue management to new drivers than in any technological approach. He believes too many drivers are coming out of CDL schools without the basics.

“Putting a camera in [a driver’s] face and knowing it’s on all the time – I couldn’t handle that,” Hoffman says. “Go back to letting the person stop and take a nap from time to time. New drivers have not learned early on enough that you don’t drive until you’re dead tired and then get some sleep. You’ll never get enough. Stop when that first or second yawn hits. If you learn to recognize the fact that your body gets tired, we wouldn’t need these cameras in your face.”